Constructing knowledge

Block play and the indoor learning environment

| August 2023I’m packing my van with loads of blocks, gearing up for another lively workshop for early educators. There's a bit of heavy lifting involved, but the excitement is undeniable!

It’s interesting to watch modern brain research catching up with the likes of Friedrich Froebel, Caroline Pratt, Harriet Johnson, Elizabeth Hirsch, and Mary Jo Pollman. Educators have always felt the effects of block play on boosting children's social, emotional, cognitive, and physical development (Hansel 2017), but exciting new research on spatial abilities can now be added to the argument for blocks in the early years.

As I walk into the nursery to deliver my workshop, I observe a five-year-old recreating in detail a village from his favourite storybook. He could not have drawn this map with pencil and paper, because his mark-making skills are not yet that advanced. However, with blocks, he is amazingly adept. If he did not have this means by which to express his ideas, adults would have no way of knowing that this child has an entire map memorised in his mind!

Problem-solving

As staff, it can be difficult to stand back when children's structures keep tipping over, but giving children time to solve their problems enables them to find their own solutions. For example, a four-year-old in block play wanted to build a bridge but seemed unable to figure out how to get the blocks to balance. His teacher could have demonstrated in an instant but held back and observed. The child eventually moved to other activities, but the challenge must have worked in his mind overnight because when he returned to the block corner the next day, he quickly placed the blocks and built bridges all over the room. He had cracked the problem and made the learning his own.

Initially young children may require support from skilled practitioners to encourage their engagement with blocks. Over time, if left free to experiment, children start using the blocks to construct interesting patterns or purposeful projects – not only roads and houses but imaginary ideas as well. Completion of structures is not the end of the play. Children often decorate a tower with beads, buttons, scraps of cloth, pine cones, coloured yarn – whatever is accessible. They might use little vehicles and human or animal figures to enact their thoughts. Sometimes these figures are just clothes-pins or plasticine people.

With a new group of children, various sizes of blocks can be attractively laid out in the construction area. Give them time to become deeply involved before bringing in baskets of natural materials, small figures and vehicles. Waiting until the children are fully engaged with the blocks allows the added accessories to enhance the experience instead of taking away from it.

Literacy

Block play is an avenue for early storytelling, as children weave narratives while constructing. Children initially playing side by side on separate constructions often interact in conversation and begin to play together, developing confidence while speaking and listening to each other.

Children may play alone or with others (EYFS). Younger children initially play by themselves, but blocks help them to build relationships alongside each other, and eventually share the space and the resources together.

Books read in the classroom can lead to marvellous constructions in the block area. For example, a fairy tale has inspired four-year-old Megan to use blocks to “draw” a knight flat on the floor. Elinor and Chloe have built a castle and now are making paper tickets so they can charge admission while Daniel is constructing a dragon. Its curving tail extends across the room. Its jaws of up-ended ramps are full of small wooden figures – the “knights” the dragon has devoured.

Ideally, constructions should be kept intact until children are ready to move on; they love to develop a theme or project over several days. But if structures must be cleared away, it is important to acknowledge them first – one child celebrated his castle by dancing around it, then he was okay with dismantling it. Some settings photograph constructions so children can show their parents.

Mathematics

Initially, mathematical thinking develops as children experiment with the size, shape, and weight of the blocks, experiencing forces and the effects of gravity. As the rules of physics are internalised, they master concepts of stability, proportion, design and symmetry. They are also experiencing, first hand, concepts such as volume, area, distance and even addition and subtraction as they add or remove blocks.

Spatial abilities

New evidence connects good spatial skills to STEM success. Dr. Jo Boaler at Stanford University implies that handling blocks and understanding their three-dimensional nature leads to robust brain pathways and a deeper grasp of spatial concepts, in contrast to merely recognising shapes on a worksheet.

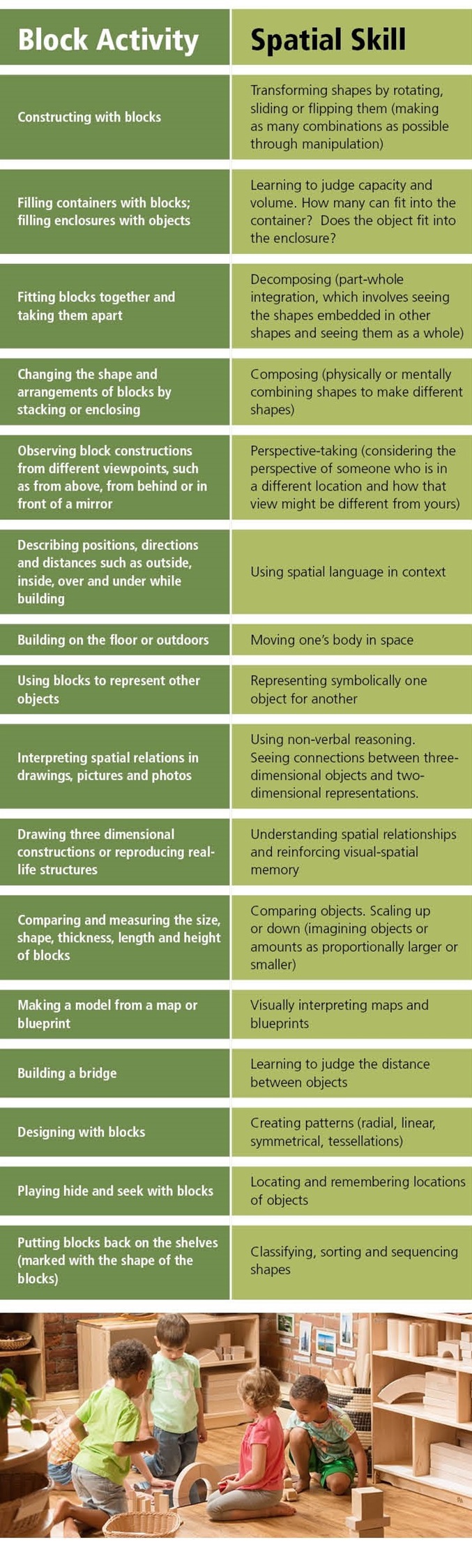

Begin by giving children plenty of time for free exploration with blocks. But don't stop there. To truly nurture children's spatial thinking, focus on the spatial abilities listed below. Incorporate block activities that promote spatial vocabulary and present challenging tasks.

References

Berkowicz, Jill and Myers, Ann. (2017) Spatial Skills: A Neglected Dimension of Early STEM Education

Boaler, Jo. (2016) Mathematical Mindsets: Unleashing Students’ Potential through Creative Math, Inspiring Messages and Innovative Teaching.San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hansel, Rosanne. (2017) Creative Block Play: A Comprehensive Guide to Learning through Building. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press.

Lubinski, David. (2013) Early Spatial Reasoning Predicts Later Creativity and Innovation, Especially in STEM Fields. Science Daily

Rosanne Regan Hansel. (2017) Blocks: Back in the spotlight again