Reaching out for inclusion

A teacher’s journal on preparing the learning environment for a new academic year

| July 2020All is quiet. I stand in the classroom contemplating my next steps. It is the summer holidays and I am preparing for a new teaching job with a class of 30 Reception children.

What do I know already?

I think about the journey so far. I have visited the children in their early years settings and practitioners have passed on their key messages about each child. At induction days parents and children have shared their concerns and hopes for the transition into school. School Entry Planning meetings have taken place for each child identified with a Special Educational Need or Disability, enabling discussion with parents, preschool practitioners, a range of multi-agency professionals and the school SENCO. Children’s interests and needs have been shared. I have the children’s starting points: data and comments in transfer documents from over 20 different early years settings. These have been read and compiled onto a cohort grid to show strengths and areas for development across groups of children, such as summer born children. This is how I begin. By reaching out for this information from all parties, I can start planning for inclusion.

The reality

Money for resources is very limited. Our space is the smallest, darkest and most cluttered classroom in the school. The children’s toilets are accessed through another classroom. Many parents have said the children are scared of the “big” and “smelly” toilets. The first thing I do is buy step stools and toilet seats to enable easier access to the toilets, whilst putting in a request for a refurbishment to age/size appropriate heights.

The outdoor area is about 20 x 30 feet, concrete and surrounded by a fence that children can climb over. There is a shed which is bursting at the seams with large plastic toys, many of them broken, and one lonely tree pulling up the concrete with its roots.

The classroom has 3 exits. The first is to the concrete outdoor area, with fences that can be climbed and a gate that the children – or anyone – can open. The second is through the practical area, which is not visible from the main room and leads to the hall. The third is a door to a small courtyard not used for play as the gate, also easily opened, gives access to the large school playground, the field, the school drive and local shops.

It is easy to feel overwhelmed by the task of preparing this environment for my class. The needs of the children in this fairly affluent area are mixed, often hidden, and not uncommon. They include a child diagnosed with autism who dislikes too much sensory stimulation, a child who constantly seeks multi-sensory stimulation, a child who is unable to find their voice in a group, and a child who simply roars at people. There is a child who has difficulty running because he spent most of his time in a pushchair and a child who “does a runner” all too often. There are several children who have recently arrived in England and speak no English yet. There are also children in the class with epilepsy, food allergies, speech and language delay and hearing loss. Some are recently bereaved, from broken homes or in temporary accommodation. As a team we consider each need in turn and work out ways to minimise risk, encourage inclusion and promote a positive transition to school.

Getting started

Safety, security and storage – securing the school site, tackling storage

I explain to the head teacher and senior staff that EYFS children must be within hearing or sight of the adult, and show them where we need better security in our space. Staff discuss solutions and taller gates are fitted with locks which still enable them to be opened quickly when needed. Some routes the older children take are reconsidered, with the youngest children’s safety prioritised. I ask for large shelves to store toys and equipment. The younger the child, the larger the toys and equipment. All early years staff are given time for the therapeutic job of sorting equipment, being ruthless about getting rid of broken or unsuitable toys. The shed is emptied, swept of years of dust and spiders webs, and fitted with shelves that enable children to access the equipment. Staff take pictures of items in the boxes, to make visual labels and then photograph how it all fits into the shed to encourage everyone to return items to a safe storage space, setting expectations for all of us. They welcome the opportunity with some relief stating how much easier their roles will be with an organised space, appreciating the permission to make changes. Some screaming at spiders and much laughter is had during this clear out. It brings the team together through a common practical purpose and the shared belief that children should be able to access and select resources independently where possible.

The outdoor areas are swept of old detritus: the shards of broken toys, long lost Lego pieces and escaped miniature animals. In the next few months, sandpits are refilled, a mud area is made, bug habitats are built, and raised gardens are planned. Funding bids are completed. A lottery donation is received and local garden centres help out with compost and plants. Grandparents and parents donate plant pots and bulbs to plant to brighten the space when spring comes. All the children participate in making wind chimes and leaf-kebab mobiles to hang under the shelter, and bird feeders for the tree. These activities are developed from children’s ideas and help them take ownership of their space.

Making room for movement – providing space for manoeuvring in a large group

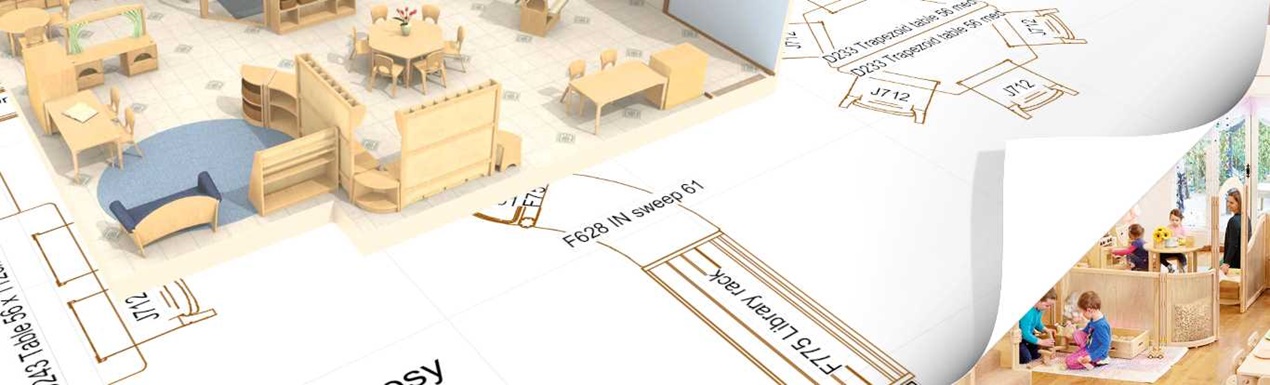

I think carefully about the lines of direction between doors, wanting to ensure ease of movement without encouraging running inside. In addition, I consider furniture that may be easy to bump into, and try to reduce risks for those children and adults who find negotiating in smaller spaces more difficult.

Resource readiness – listening to those who know what the children like and need

All cupboards and drawers are cleared and cleaned, and resources are carefully selected to meet a range of needs and interests. I refer to my notes of interests given by parents and practitioners, trying to ensure there is something which provides continuity and familiarity for each child. All labels are refreshed with a mixture of words and photographs. Resources are organised around skills such as hand-eye coordination or positioning and comparison. I opt for less resources whilst allowing for progression, for example: simple inlay puzzles for children struggling with fine motor skills to 100-piece jigsaws for children requiring further extension.

Noticing and allowing the emotions of transition

Creating more space enables parents to come in each day and engage in an activity with their child in order to settle them. There is room for goodbye hugs, as most children settle well when they have had time to say goodbye. I encourage children to select a cuddly toy or bring one from home to support transition if they wish. One child needs to hide first and be in a space that feels more secure, so in discussion with him and his parents I set up a space under a table near a staff member. Here he can play with favourite items, see out through the voile fabric and come out when ready, which is usually when the other children have moved away a bit. With this need acknowledged, he quickly progresses to greeting his small circle of friends on arrival, growing in social confidence every day. This child was extremely shy and hardly spoke at all to start with, but through working with his family and enabling him to have choices he became much more confident, achieving all his developmental milestones for a Good Level of Development at the end of the EYFS. He just needed time and for staff to take steps to include him, working from his unique starting points.

Sensory area – seeking, selecting, spinning, sparkling

I prepare a small area of the classroom as a mini-sensory space, entered through a hanging screen, with baskets of sensory toys that light up or spin. A reflective surface brightens the dark corner with some sparkly and shiny items like glitter sticks, tinsel and shiny fabric squares. This allows children to seek sensory feedback and select items themselves, and provides an opportunity to de-regulate emotions through sensory experiences. It was a new idea to the school and children came from other classes with an adult to explore the space. One day a child from Year 6 left her class to come to the sensory area, demonstrating her need for using sensory items to help de-regulate and calm her. These strategies were able to be shared and developed with other staff by teaching assistants directing their own professional development.

Final thoughts

Listening to the children, observing their needs before they start school and inviting further opportunities for independence once they start, is a powerful way to include all children. Sometimes inclusion is simply enabled by taking a step back, looking at the environment through the lens of the children and problem-solving before they arrive to meet some of those needs. It’s about observing their use of space and adapting it for them to enhance language and social skills. Ensuring children feel safe and ready to play and learn in their new classroom is time well spent and can enable more rapid progress later in the year. Inclusion, to me, is about reaching out and inviting in; in the words of Winnie the Pooh “You can’t stay in your corner of the forest waiting for others to come to you. You have to go to them sometimes.” (AA Milne)