Designing quality child care facilities

| June 2012The importance of physical environment in child development

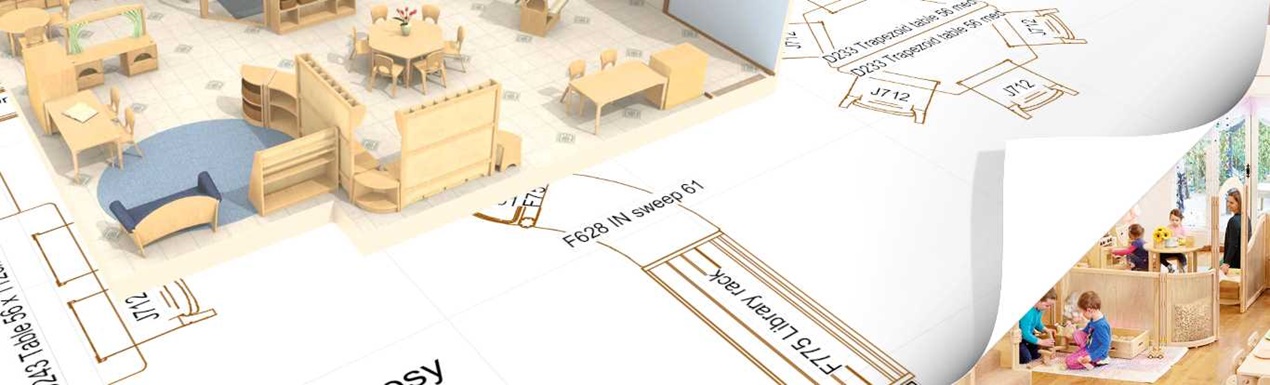

The physical environment can either contribute to children's development and support staff and parent goals or create a permanent impediment to the operation of a high-quality program. Designing a high-quality, developmentally appropriate child care facility is a highly complex task which requires specialized and unique skills. The design and layout of the physical environment, which includes the building, interior finishes, outdoor spaces, selection of equipment and room arrangement has a profound impact on children's learning and behaviour and on teachers' abilities to efficiently do their jobs.

Children need age-appropriate physical environments that support and promote child-directed and child-initiated play. The environment must promote and positively support the child's interaction with space, materials and people. Teachers and caregivers also need highly functional, easy-to-use environments. When the environment supports both and is working for children and adults, it is easier for adults to focus on facilitating each child's play and learning.

Common pitfalls in designing child care facilities

Facilities that fail to support a high-quality program are usually the result of well-meaning intentions gone awry. The problem can usually be traced to both the expertise of the design participants and the design process. The product can only be as good as the process that creates it and the expertise of the design participants.

The first problem is that architects and designers who understand the principles of design often have little knowledge of child development and the operation of child care centers. Many times architects and designers create and choose designs that look good to them but may not be functional and practical in a child care center. Some buildings end up being architectural monuments that are over-designed with too much of the money being spent on the outside facade.

The more money that is being spent on the exterior shell of the building, the less money there will be for inside functional details like high-quality finishes, appropriate furniture and equipment, adequate numbers of sinks and interior windows/doors - all details which can better support children and staff needs.

Challenges in translating child care expertise to design

The second problem that contributes to poor design is that the directors and teachers who know children and understand their needs rarely know how to translate their teaching and administrative skills to the design of space and the language used by architects and designers. Most child care practitioners may not be able to offer the best design solutions because they do not have a broad enough experience base. Due to being hampered by their existing paradigms, practitioners may be unaware of many solutions or may not be able to understand the downside of a particular solution.

Sequential vs. Concurrent design approaches

The third problem that contributes to poor design has to do with the design process itself. The traditional design process is sequential like a relay race. The architect grabs the baton from the client, does the site and floor plan and passes the baton to the structural engineer. The structural engineer finishes their job and starts the baton on its path to a long line of specialists who, one by one, create the lighting, electrical and mechanical systems and interior design. Then the baton is passed to the staff to select and lay out the equipment.

One of the big problems with this sequential relay approach is that each stage of design squeezes the stage after it, often closing off options that could have improved quality, reduced costs and sped up construction. Another problem is that each person has a vision only of his or her brief segment of the race; there is no unified vision to guide the design.

Best practices for child-centric design

Our company believes that high-quality, developmentally appropriate facilities are created through what is called concurrent design. Concurrent design means pulling together all the experts who design the facility and those who operate it at the same time. Everything impacts everything.

Function is examined in the process prior to looking at form. For example, many programs such as Head Start encourage parents to work in the classroom. Parent participation may necessitate more classroom square footage than state licensing standards require. State licensing requirements are only minimums and not necessarily quality standards.

The design team needs to be structured and sensitive to staff, parental and community input. The team should have members with specialized expertise in various areas. Whether you are working on a renovation or planning a new facility, the design process has a number of steps which are important for the practitioner to understand.

Designing and creating a high-quality child care facility is a complex and lengthy process. By understanding the multi-faceted issues and complexities of designing children's environments, you can better select and work with a qualified design firm that can deliver the high-quality, comprehensive and integrated design solutions that are required for a child care facility to meet staff's, parents', community's and children's needs.

References

Greenman, Jim, "So You Want to Build a Building? Dancing with Architects and Other Developmental Experiences--Part 3: Designing the Building", Living in the Real World, Child Care Information Exchange 1/92, Vol. 83, Pages 47-50.

Greenman, Jim, "Why Did It Turn Out This Way? How Buildings Go Wrong", Living in the Real World, Child Care Information Exchange, 3/92, Vol. 84, Pages 49-51.

Copyright © 2007 Vicki L. Stoecklin & Randy White. Reprinted with permission.