Wabi sabi for children

Simplicity in early years environments

| February 2021The Japanese tradition of wabi sabi has much to offer as we look to create a more thoughtful and sustainable way of educating our young children. In this article, we attempt to bring a wabi sabi lens to our physical surroundings within the early years setting.

Simplicity and space

Traditional Japanese design has long been associated with a simple, uncluttered, minimalist aesthetic. Clear spaces, natural substances and a limited number of carefully chosen and arranged items make up the hallmark of the wabi sabiesque living environment.

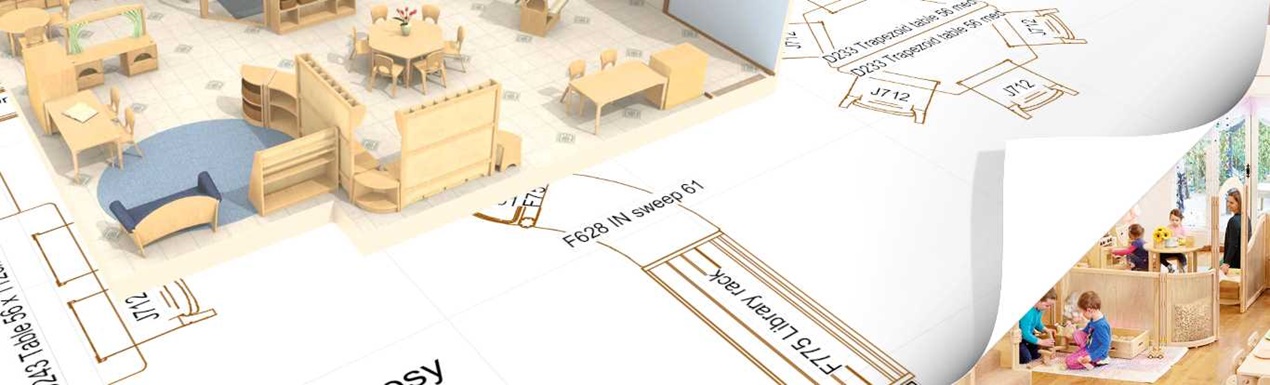

Many of these design principles chime with the pedagogical philosophy underlying Maria Montessori’s ‘prepared environment’. Through her empirical studies of young children, Montessori observed that ‘interest and concentration arise specifically from the elimination of what is confusing and superfluous’ (Montessori, 1982).

In line with this observation, Montessori decreed that there should only be one of each piece of equipment in a Montessori Children’s House, and that every resource should be displayed to its best advantage, in order to attract the child’s attention. We have no way of ascertaining whether Montessori knew about wabi sabi, but the pedagogy underlying many of her methods is strikingly reminiscent of its philosophy.

Using ‘simplicity’ as one of the key principles for organising the early years setting can be surprisingly straightforward to put into practice, and it also brings many benefits to children’s well-being and development:

- Freeing up as much clear space as possible and decorating it with neutral colours creates a calming backdrop for the busy life of the setting

- Simplifying the number of resources on offer enables children to see more easily what is available to them

- A calm, spacious environment is less overwhelming and confusing than a busy, cluttered setting

- The less ‘stuff ’ you have out, the easier it is to create eye-catching arrangements and display resources to their best advantage

- Keeping back resources allows you to change what you make available, enabling you to spark fresh interest and introduce new challenges

- It is easier to clean a simple, uncluttered environment than an overfilled space – of particular importance during a global pandemic!

Treasured belongings

Reframing our attitude to ‘things’ makes a useful contribution to the de-cluttering process. In her definitive book on wabi sabi for the Western readership, Beth Kempton suggests that we should stop regarding open shelves as storage, and start seeing them instead as the home for treasures (Kempton, 2018).

The wabi sabi tradition of seeing beauty in the mundane and everyday is also important. Our treasures do not have to be rare or expensive, especially if they are displayed with care. Kempton describes hanging her linen apron on a hook in her kitchen, and so making this everyday object a thing of beauty (Kempton, 2018). In the environment of the early years setting, it’s surprising how shifting the position of a seldom-used resource, or grouping it with other objects to create a Reggio Emilia-style provocation, can spark new interest among the children.

Assessing the details

The creation of a calm, uncluttered space is an important aspect of wabi sabi-inspired design. It is, however, attention to detail that brings a truly wabi sabiesque aura to the setting.

To bring a wabi sabiesque attention to detail to your setting, consider the following:

- How do things look in relation to each other? Do you have small windows or skylights that act as a frame to create an outdoor picture? How does the picture change with the weather, time of day or seasons? What can be seen beyond the frame of an open door, and how does this picture change? Draw the children’s attention to these visual relationships and wait to see what they make of them (a game of peepo through the door, perhaps?)

- When arranging items and resources, consider how they balance each other visually. Look at different ways of combining horizontals and verticals; for example, tins of coloured pencils (verticals) and wooden pencil boxes (horizontals). Explore arranging items according to ‘the rule of three’. This is based on the theory that odd numbers attract the eye because they look more dynamic and less staged than even numbers.

- The wabi sabi approach to colour focuses on naturals and neutrals. This makes a great backdrop for splashes of colour. Try to avoid grouping lots of brightly coloured resources together, instead placing just one against a neutral background (a plain wooden shelf, a cream painted wall). This will draw the children’s attention far more effectively than a jumbled mass of colour.

- Choose secret places for small items – a tiny picture on the wall above the skirting; a family of miniature toy mice in a corner behind the book box; some colourful polished crystals tucked in a basket of pebbles. Make a list of ideas, ring the changes, and give the children hints when there is a new hidden treasure to look out for.

- Check whether items are getting old and worn. Can you repair them, to avoid having to buy new? Involve the children in mending, and celebrate how you have all worked together to give this well-used item a new lease of life.

Observations and audits

Making regular observations and auditing your environment and its contents are key to bringing a wabi sabi lens to the setting. Use observation to discover how your spaces work in practice, and which are the least popular activities. Use auditing to assess whether you have duplications or superfluous resources. Based on your observations and audit, introduce flexibility so that the environment can change according to the needs of the children and the shifting seasons. Once changes have been made, observe closely to ensure that they are functional.

Bring nature indoors

Numerous studies show the important role that nature has to play in reducing children’s stress levels and promoting learning. Positive effects appear to stem from more than just the increased physical activity associated with spending time outdoors, important though this is.

For example, a 2016 study showed that a classroom window view of vegetation had greater capacity to reduce heart rate and stress levels among children, compared with a view of the built environment (Liu and Sullivan, 2016). Although the study looked at older children, it is likely that the positive systemic impact of the natural view can be applied to all age groups.

Studies such as these underline what the ancient philosophy of wabi sabi has always known – that bringing nature indoors and creating a seamless passage between indoors and outdoors are vital to our health and well-being.

Thanks in part to the Forest School movement, early years settings are already developing a wabi sabiesque relationship with nature. Creating interesting outdoor spaces, breaking down the barriers between indoors and outdoors, and bringing nature inside are all strategies that fit comfortably with the wabi sabi philosophy. To add further depth and subtlety to the presence of nature in your setting, try the following wabi sabi-inspired ideas:

- Find ways of bringing light and weather indoors. For example, do you have a window through which beams of sunlight dapple the floor, a corner where shade deepens as the sun goes in or patio doors that look out across a shrubbery? Where possible, make sure that furniture does not obstruct such spaces and draw the children’s attention to these natural phenomena.

- Beth Kempton describes the seasons as ‘a kind of wabi sabi metronome’, and explains that the four seasons are ‘woven into the fabric of everyday life’ in Japan (Kempton, 2018). Mirror this engagement with the changing seasons through nature displays, choosing seasonal colours for cushions, blankets, rugs and artwork, eating seasonal food and celebrating festivals that reflect the natural essence of each season.

- The transience of weather is important to wabi sabi because it reminds us to be present in the moment. Help children to notice the weather and its changes. Be aware of how weather and the seasons affect children, and allow the weather to dictate behaviours and activities. If windy days make your group ‘buzzy’, spend time outdoors dancing with the wind. Be slow and lazy like cats when the weather is very hot, and cuddle up cosily for stories on a grey winter afternoon.

- Use nature and natural items to bring a variety of textures into the setting. Wood shelving and floors, coir doormats, ceramic tiles, marble blocks, metal, wood, terracotta and wicker containers, linen, cotton and woollen curtains, rugs and cushions are just some of the natural substances that introduce texture – and are generally more eco-friendly than synthetic materials.

- Bring nature indoors with flowers, foliage, twigs, bark, grasses, feathers, pebbles, shells, rocks, crystals, pine cones, conkers, nuts and seeds. Use the nature items to reflect the seasons and create interesting provocations.

As with any complex philosophy, it is important that we do not fall into the trap of interpreting wabi sabi as prescriptive – particularly with regard to creating wabi sabiesque surroundings. Enjoying each stage of life for its own sake is central to the wabi sabi philosophy. Whether you choose to draw on many or just a few of its guiding principles, the truly wabi sabiesque environment should reflect the uniqueness of you and your children, and resonate with the joy, wonder and eagerness of early childhood.

This article was first published in the November 2020 edition of the Early Years Educator (eye) magazine.

References

Kempton, B. (2018) Wabi Sabi – Japanese Wisdom for a Perfectly Imperfect Life, Piatkus

Li, D., and Sullivan, W. C. (2016). Impact of views to school landscapes on recovery from stress and mental fatigue, Landscape Urban Plan

Montessori, M. (1982) The Secret of Childhood, Random House